We all associate ageing with more wrinkles, greying hair, or finding it a little harder to spring up from a deck chair.But what does ageing look like in our cells?

If you zoom in on a single cell, you'll find a hive of activity. Messages will be coming in and out and the cell will assemble new proteins, break down waste products and produce energy. Occasionally, it may copy its genetic material and divide, producing new cells.

As we get older, some of these processes begin to break down. Here are a few of the ways this can happen.

Cellular Wear and Tear - How?

Most of a cell's activity is driven by an internal instruction manual: its DNA. How that instruction manual is read differs from cell to cell, thanks to highlighters that point out which parts of the manual apply, a process calledepigenetics.

Over time, our cells get exposed to environmental triggers likesmoking or UV light, which can influence which parts of our DNA get ‘read’ by cells.

One epigenetic marker that increases as we age is called methylation. Scientists have even coined the term‘epigenetic clock’, as you can tell how old someone is by looking at how methylated their DNA is. In skin cells, methylation has been shown to affect how cells function, slowing the production of proteins important in maintaining skin elasticity, amongst other things. And when the cell divides, these markers are passed on, affecting the behaviour of the next generation of skin cells.

IMPERFECT DIVISION with Cells As You Age

Another consequence of copying DNA, again and again, is the accumulation of mistakes or mutations. Mutations can make cells work less well. And while cells are really good at coping withmutated cells, ultimately too muchDNA damage will overwhelm them.

Mutations aren't the only risk. It's impossible for a cell to copy the information right at the end of a strand of DNA — the end of each chromosome — so every time a cell divides, sections of DNA are lost. To compensate, our DNA has a repeated sequence of 'junk' DNA at the end of each chromosome, called telomeres.

There’s a lot of DNA that can be lost from telomeres without causing damage. But each time a cell divides, itstelomeres shorten until there's no protective buffer left and the cell must take evasive action to avoid damage to important sections of DNA.

EVEN HEALTHY CELLS DIE

What happens to a cell's DNA over time (and after multiple rounds of division) is a big part of the ageing process, but it's not the only part. Like any complex piece of machinery, different parts get damaged or worn by overuse. Protein assembly and energy production become less efficient, and waste products start to build up.

All of these processes push a cell toward self-destruction or a permanent withdrawal from the cell cycle, a state calledcellular senescence. These are important safety nets for the body, ensuring faulty cells don't keep dividing and the damage ends with them. A skin cellmay only live 2 to 3 weeks and that's OK because there are other cells dividing to pick up the slack.

Cell death or senescence becomes a bigger problem when cells no longer replace themselves. This means fewer and fewer ‘fresh’, healthy cells which, when it comes to our skin, is seen asthinner, more fragile skin.

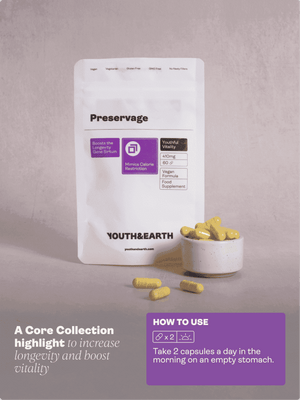

SLOWING CELLULAR AGEING

By understanding ageing processes in different cells, scientists can learn which environmental triggers to avoid and identify interventions that could interrupt ageing processes.

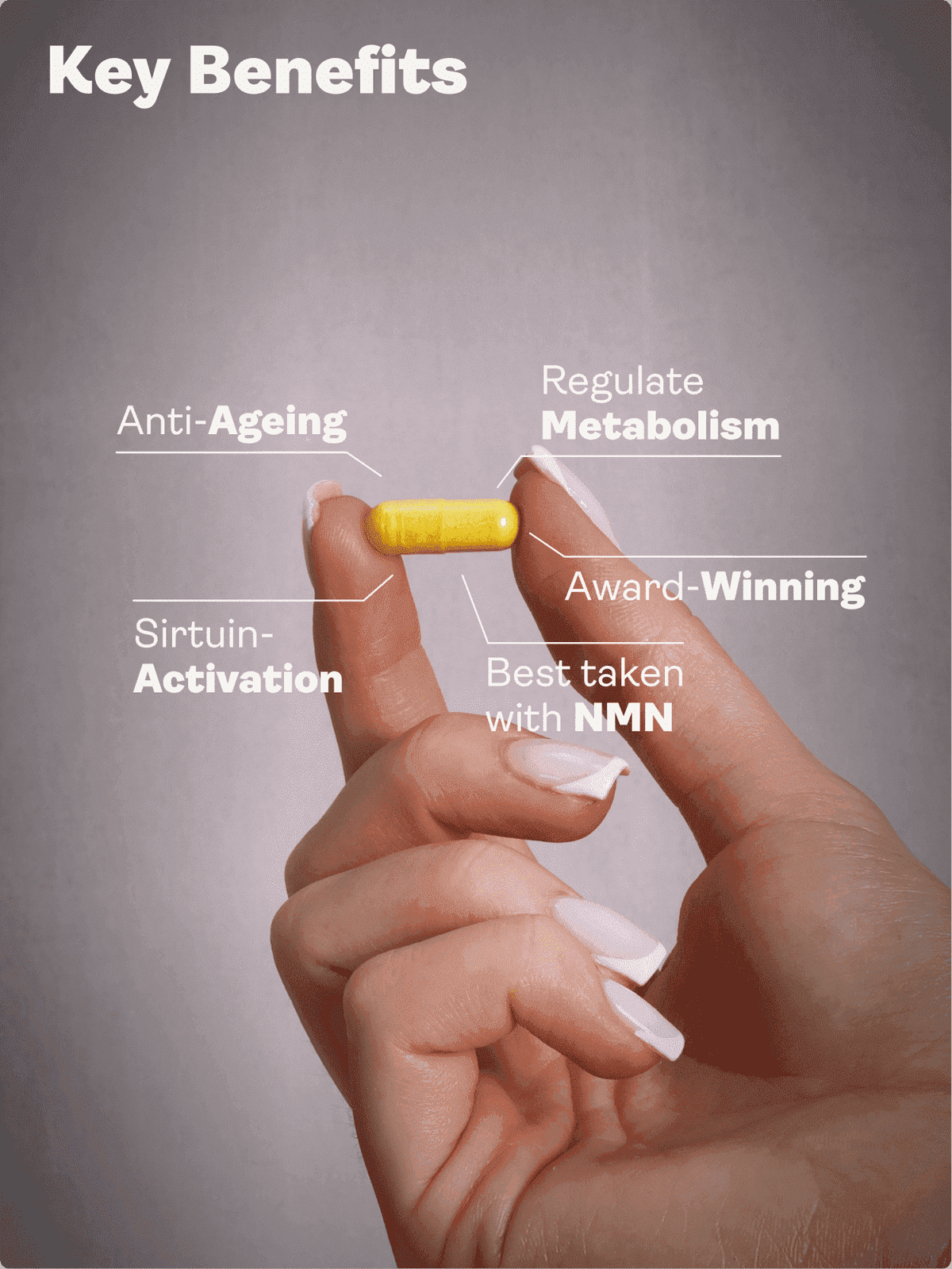

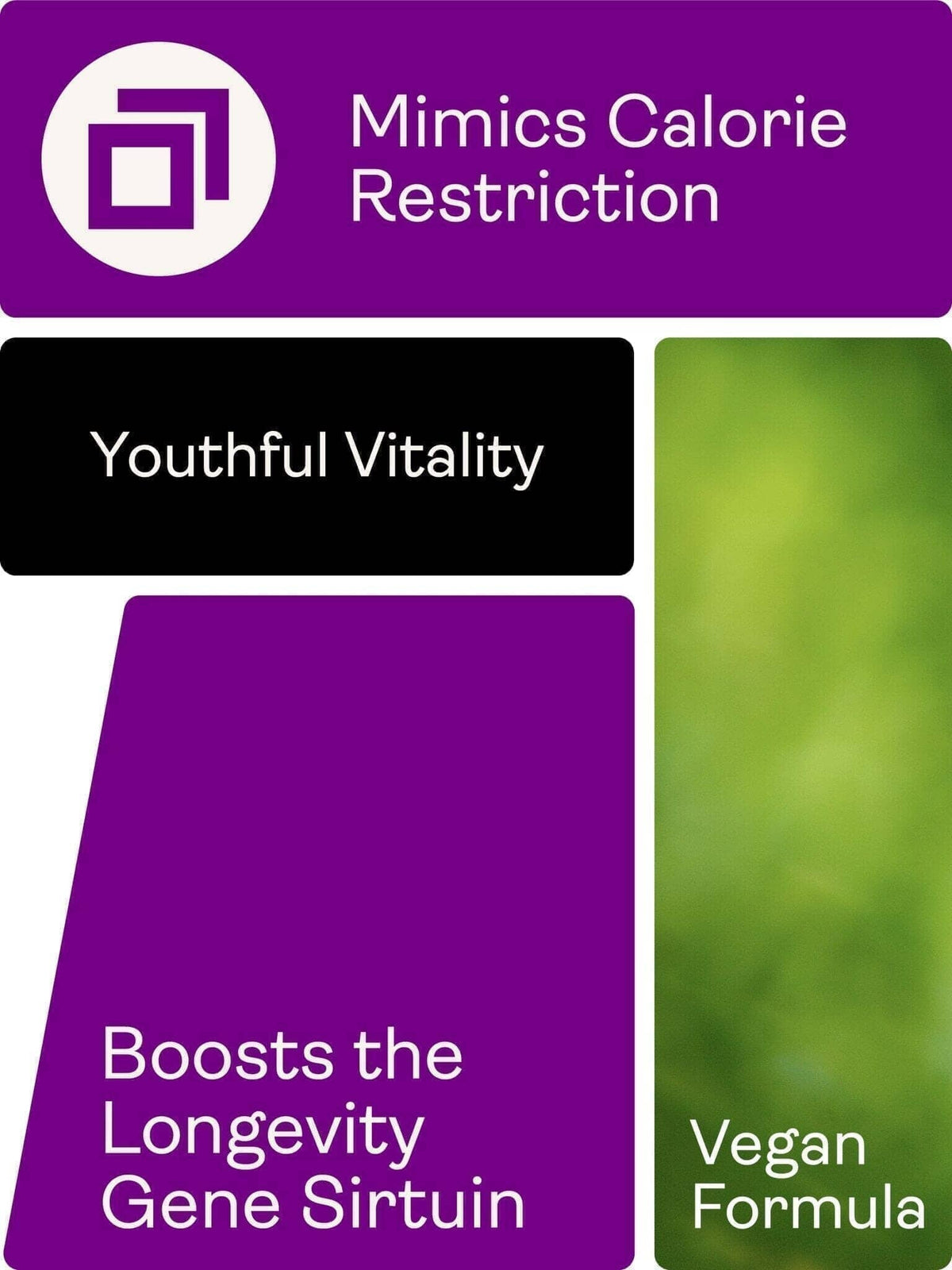

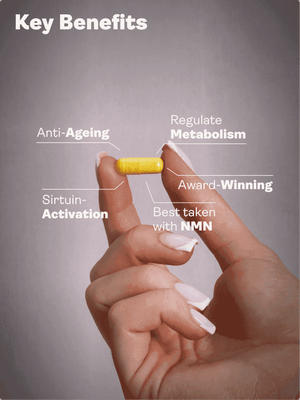

Take epigenetic changes. Scientists have discovered a family of seven proteins called sirtuins that help regulate epigenetic changes to our DNA, including in our skin cells. But as we age, levels of sirtuin drop. Understanding how to increase the levels of certain sirtuins, and the molecule it needs to function(NAD+) is a key focus for researchers.

Ageing is clearly a complex process. Our cells are hardworking machines, and like any machine, over time parts begin to fail. Understanding which parts falter, and how to fix them, will play a key role in achieving longer, healthier lives.

Join us forPart 4 as we explore how human longevity has evolved over time.

It’s not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or health provider before starting a new health regime or program.

Do not ignore medical advice or delay seeking it because of something you’ve read on this site or any Youth & Earth product.